Nov 27, 2020 | Article

Outsiders often assume that trustees have both the authority and the capacity to enter into transactions binding the trust. If trustees have not ensured that these requirements are met, to what extent can outsiders be deemed to have known?

In the instance of companies and close corporations, the Courts have adopted a principle called the “Turquand Rule”, which provides that a contracting party, who was dealing in good faith, can assume that acts have been properly and duly performed and that the required approvals were obtained, subject however to the requirement that those acts have to be within the company’s constitution. Section 20(7) of the Companies Act 71 of 2008 provides that a person dealing with a company in good faith, is entitled to presume that the company, in making any decision while exercising its powers, has complied with all the formal and procedural requirements in terms of the Companies Act, the company’s Memorandum of Incorporation (MOI) and any rules of the company, unless, in the circumstances, the person knew or ought reasonably to have known of any failure by the company to comply with any such requirements.

There is no such equivalent provision in the Trust Property Control Act. The Court in the van der Merwe NO and Others v Hydraberg Hydraulics CC and Others, van der Merwe NO and Others v Bosman and Others case of 2010 held that the “Turquand Rule” could not be applied to the trust, because the trust instrument did not provide a power to the trustees to authorise one or more of them to make decisions on the board of trustees’ behalf, or to act as principals in respect of the trust’s affairs, without acting jointly with the rest of the trustees.

In the Nieuwoudt v Vrystaat Mielies case of 2004, the Court held that the powers provided to the trustees in the trust instrument only related to the fact that they could sign on behalf of the rest of the trustees; not that they could make decisions on behalf of the board of trustees.

The Court held in the Land & Agricultural Bank of SA v Parker case of 2005 that “within its scope the rule may well in suitable cases have a useful role to play in securing the position of outsiders who deal in good faith with trusts that conclude business transactions.”

It is advisable for those dealing with trusts to assume that the rule does not apply to trusts in the present state of South African law. The liability is therefore on the outsider to ensure that due process was followed, unlike where one deals with a company, in which case the company will be bound even if, for example, the director lacked authority because the internal requirement of delegation had not been met.

What about property transactions?

Contracting parties are particularly cautious in the case of the purchase or sale of immovable property. In terms of the Land Alienation Act, any deed of sale of immovable property has to be in writing, and the parties thereto or their agents have to be legally authorised to act at the time of signing of the contract.

The Thorpe v Trittenwein case of 2007 confirmed the principle that where one trustee is authorised to act on behalf of other trustees, and the sale of land is involved, such authorisation must be received in writing in the form of a resolution duly signed by duly authorised trustees by the Master of the High Court. Any deed of sale entered into by one trustee purporting to act on behalf of other trustees, where that trustee is not authorised to do so by their co-trustees, may be deemed null and void. This is because it will not comply with the requirements of the Alienation of Land Act (Section 2), and cannot be ratified thereafter. This case confirmed that a sale cannot be ratified by the signature of a written authorisation to act after the fact. The written authority, therefore, must be granted prior to the signature of the deed of sale to the duly authorised trustee.

What should a contracting party do?

· View the Letters of Authority from the Master authorising the trustees to act

· View the trust deed to make sure that the board of trustees is properly constituted and has the capacity to enter into the type of contract in question

· Ensure that all internal formal or procedural requirements have been met such as a resolution authorising a trustee to sign a contract on behalf of the trust.

This is a useful article written by Phia van der Spuy

-Ant Jenkins

Nov 11, 2020 | Article

The SARB is moving away from the concept of emigration. This will necessitate changes to the Income Tax Act which has references to emigration in relation to taking retirement fund amounts out of South Africa.

Currently, if you formally emigrate, you are permitted to cash in your retirement funds entirely as part of the emigration process and, having paid the requisite taxes, take the funds with you.

The 2020 Tax Laws Amendment Bill includes proposed amendments which now refer to a person’s tax residence rather than emigration. If passed into law, from 1 March 2021, it will only be possible to export the proceeds of retirement funds three years after ceasing to be a tax resident. The onus of proof is on the taxpayer in this matter but we would like to mention that currently one can indicate on your tax return that you consider yourself not to be a tax resident. Given this situation it will be difficult to argue that you ceased to be a tax resident prior to making this declaration.

In any event it should be borne in mind that ceasing to be tax resident is a CGT event and that will trigger payment of CGT on all taxable assets where a gain in value exists at that date. No sale of assets is required for this to be the case. It has been common practice among Saffers who are working abroad to merely relocate and not formally emigrate. Those who do not expect to return to South Africa and who may want to access retirement funds within the next three years should consider formalising emigration under the current laws prior to 1 March 2021.

The CGT implications should be borne in mind.

There may also be those who currently reside in South Africa but who are thinking of emigrating. To the extent which they are practically able to do something about the date of their emigration they may wish to consider these new proposed tax laws.

(Source: Rob Evans – Surelink Wealth)

Nov 6, 2020 | Article

Often the testator or testatrix directs in his or her will that his or her assets be transferred into a trust to be formed upon his or her death. A testamentary trust is then formed upon his or her death and the terms of the last will and testament form the terms of the trust.

Unlike an inter vivos trusts, which is a contract, which the contracting parties (the founder, the trustees and potentially the beneficiaries) can amend in terms of our law, the trustees cannot amend the trust instrument of a testamentary trust on their own, as one of the contracting parties – the founder – is no longer around.

Freedom of testation

In South Africa, the legal principles applicable to a testamentary trust are to be found in the law of testation, unlike that of inter vivos trusts, which are to be found in the law of contracts (Crookes v Watson case of 1956 and the Braun v Blann & Botha case of 1984). An individual therefore has the right to determine the heir(s) to his or her property upon his or her death as he or she wishes (called ‘freedom of testation’), even if such a bequest is unpopular, as long as the person making the bequest is of sound mind. An aggrieved beneficiary can therefore not have the trust instrument (the last will and testament) amended to include him or her.

Testamentary power

Each person in South Africa also has a right to exercise his or her testamentary power. A delegation of testamentary power is not allowed in South African law and any clauses in the last will and testament that are regarded as amounting to a delegation of testamentary power will be invalid. That will typically be the case where the testator or testatrix allows trustees to act as they wish and allow them too wide discretion (Braun v Blann & Botha case of 1984). Trustees in a testamentary trust should merely be allowed to exercise the instructions of the testator or testatrix as provided for in his or her last will and testament.

The role of the Court

A Court can, generally speaking, also not vary the terms of a testamentary trust. Section 13 of the Trust Property Control Act, however, allows a trustee or any other interested person (beneficiary) to apply to Court to have a testamentary trust amended in specific circumstances. Any applicant will however have a hard time to explain what the intention of the founder – the testator or testatrix – was, or what he or she foresaw outside of what the trust instrument – the last will and testament – stipulates. Circumstances would probably have to change materially before anyone would be able to convince a court that there are consequences, which the deceased did not contemplate or foresee, which now negatively impacts the beneficiary/ies.

The Master’s Directive

The Master of the High Court also confirmed in a directive issued in March 2017 that a testamentary trust cannot be amended by the trustees and beneficiaries of the trust, although beneficiaries may renounce their rights. This may cause the trust to collapse and defeat the objective of setting up the trust. It may be better for the beneficiary/ies to renounce their rights and gain control over assets rather than having a trustee decide over these assets as planned by the testator or testatrix. The testator or testatrix should keep this in mind when drafting his or her last will and testament.

~ Written by Phia van der Spuy ~

Nov 5, 2020 | Article

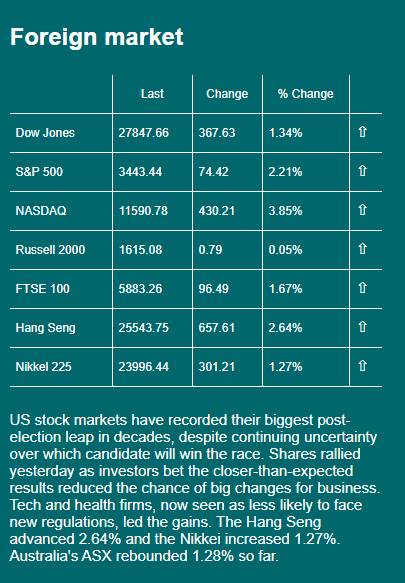

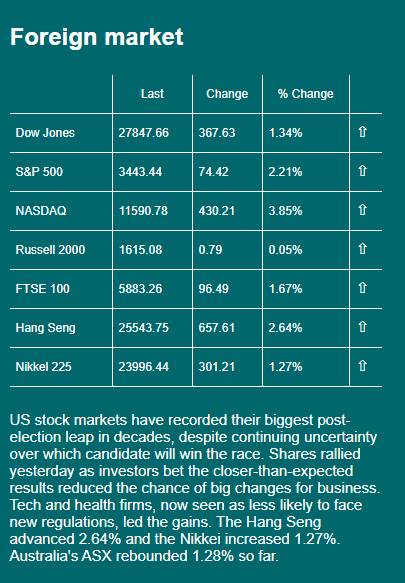

US stock markets have recorded their biggest post-election leap in decades.

Nov 4, 2020 | Article

A trust itself cannot sue or be sued, because it is not recognised as a legal persona, but rather a legal persona sui generis (which means of its own kind or class), in South Africa (Rosner v Lydia Swanepoel Trust case of 1998). The trustees, in their official capacity, can, however, sue or be sued. All the trustees must join in suing and all must be sued (Mariola v Kaye-Eddie case of 1995). Therefore when a trust is sued or sues, the names of all trustees, rather than the trust itself, are to be sited in pleadings. Even though the names of the trustees will be cited in any action against a trust, it is the trust that will be liable in respect of any claims and not the trustees personally; the trustees merely act in their official capacities as trustees of the trust.

As a general rule, the proper persons to act on behalf of a trust are the trustees, and not the beneficiaries, as they do not have locus standi (a right to appear in a court or before any body, or a right to be heard) (Gross v Pentz case of 1996). Not even a beneficiary’s interest in the trust is sufficient to create locus standi to institute proceedings against parties dealing with a trust, other than against trustees, to protect or recover trust assets (Mariola v Kaye-Eddie case of 1995).

The Gross v Pentz case of 1996, where a trustee has alledgedly disposed of a trust asset below its market value, causing financial loss to the trust, resulting in an action in respect of maladministration of the trust, amounting to a breach of trust and resulting in a monetary loss to the trust, confirmed that there are two types of actions that can be taken:

“Representative actions” – actions brought on behalf of the trust, including:

· to recover trust assets; or

· to nullify transactions entered into by the trust; or

· to recover damages from a third party

The general rule described above applies to these actions. If the trustees properly authorise one of them before action is instituted, then that trustee can act on behalf of the others (Mariola v Kaye-Eddie case of 1995). If one of the trustees, not so authorised, has initiated litigation, his or her actions can be ratified later, subject to the requirement that such trustee had the capacity to act – he or she was authorised by the Master of the High Court in terms of Section 6 of the Trust Property Control Act and the required minimum number of trustees were in office as stipulated in the trust instrument (Pieters Family Trust v PW Colyn case of 2006).

“Direct actions” – actions brought by a beneficiary in his, her or its own right against a trustee for one of the following:

· maladministration of trust assets, resulting in a loss to the beneficiary; or

· failure to pay or transfer to a beneficiary what is due to him, her or it under the trust; or

· paying to or transferring to one beneficiary what is not due to him, her or it

The Court held that only beneficiaries with vested rights can bring a direct action and not a beneficiary with merely a contingent right to income and/or capital (Estate Bazley v Estate Arnott case of 1931). This is because a discretionary/contingent beneficiary will be unable to show that he, she or it personally sustained financial loss, as such beneficiary merely has a ‘spes’ (hope) to receive something from the trust in future. The best such a beneficiary could do is to motivate that the trust sustained a loss as a result of some maladministration, which may result in such beneficiary receiving less in future from the trust, as a result of the diminution of trust assets.

Although the general rule normally applies, in this case the Court however applied the exception to the general rule and allowed the beneficiary to bring the action, as a defaulting trustee cannot be expected to sue himself (this is called the “Beningfield exception” (Benningfield v Baxter case of 1886)) – it therefore modified the general rule, which allowed the beneficiary to bring a representative action as an exception.

It allowed the discretionary beneficiary to bring the case,

as it believed that all beneficiaries have a vested interest in the proper administration of the trust.

The Court therefore confirmed that the beneficiary had the requisite locus to institute the application (this was also confirmed in the July v Mbuqe case of 2017). The Court held that the only alternative to allowing the Benningfield exception would be to require the aggrieved beneficiary to sue for the removal of the trustee and the appointment of a replacement trustee with the hope that the new trustee would bring action against the removed trustee for the recovery of the trust’s assets, or other relief for the recoupment of the loss sustained by the trust. This would impose too cumbersome a process upon the aggrieved beneficiary. The Benningfield exception would however only apply when a beneficiary had no recourse to direct action against the defaulting trustee (Breetzke v Alexander case of 2015).

~ Written by Phia van der Spuy ~

Oct 29, 2020 | Article

Given the commitment to fiscal consolidation, tax increases of R40bn will be necessary over the next four fiscal years. Taxes are set to increase by R5bn in 2021/2022, R10bn in 2022/23 and R15bn in 2024/2025. The most effective taxes to increase would be personal income tax, which contributes 30% to government revenue and VAT which contributes approximately 25%. Other forms of taxes could also be implemented such as a wealth tax, which would be politically palatable, but can be difficult to implement. A three-year solidarity tax on high-income earners has also been mooted to help pay for the Covid-19 crisis. New tax policies will be announced in the February 2021 Budget.

(Source: AdviceworX)

Recent Comments