Dec 2, 2022 | Article

The timelines for winding up an estate have improved since the peak of the Covid-19 pandemic but are still likely to take longer than before Covid, as pandemic backlogs and other problems persist.

A year was a good expectation for an estate where the deceased left a sound will and the estate was dealt with by an experienced executor, Angelique Visser, Fiduciary Institute of Southern Africa (FISA) National Councillor, says.

During the pandemic, however, timelines deteriorated, making it common for any estate to take two years to wind up, FISA reported last year.

Increased deaths during the pandemic were responsible for much of the delays, but the offices of the Master of the High Court (the Master’s Offices) also took much longer to issue the letters that appoint executors, approve the estate accounts and authorise the distribution of estate assets to the heirs.

Bank delays frustrate estate professionals

Recently FISA has expressed its frustration with delays caused by banks and banks have admitted they too were slowed up by Covid and are still catching up.

To wind up an estate, the executor of the estate needs information about, among other things, your deceased family member’s bank accounts and investments.

The accounts then need to be closed and the balances or investments transferred into a bank account in the estate’s name.

The executor also needs the tax certificates for those accounts in order to file the deceased’s tax return and the estate’s return.

The chairperson of FISA, said banks are dragging their feet on these three tasks.

He says banks have different procedures which they sometimes change without consultation, leading to confusion among bank staff, as well as much frustration for FISA members trying to help families wind up estates.

Months to respond

Practitioners are now able to obtain a letter of executorship from the Master’s Office within two to three weeks, but then battle for three to four months for a response from some of the banks.

She says she has approached the senior management of several banks for assistance but there has been no improvement.

The chief executive officer of FNB Fiduciary, says COVID-19 negatively affected the industry’s processes for winding up deceased estates.

In addition to the increase in deaths, there has been an increase in fraud and administrative hurdles that are frequently beyond the control of executors and/or banks.

Banks are working through the Banking Association of South Africa with the Chief Master’s Office to address the challenges and minimise the adverse impact on the families of those who have died.

FNB is also trying to shorten the time it takes to wind up estates by increasing its capacity to help its clients and improving the processing of smaller estates using digital platforms, she says.

Two weeks to close account

Once the correct documents have been submitted, it should take 14 days to close an account and pay any money into the estate account.

Delays are primarily due to outages on the Master’s Office portal that banks and estate practitioners use and the need to get all the necessary documents from different parties. All of this has been compounded by the large volumes of estates currently experienced.

During the peak of the pandemic the Master’s Offices worked at 50% capacity and closed frequently when staff became ill. The offices and the Department of Justice’s computer system also suffered a ransomware attack in July 2021.

IT problems

The Master’s Offices are now open but continue to be plagued by computer problems, the recent FISA conference heard.

Martin Mafojane, the Chief Master of the High Court, said the Masters Offices do not have stable and reliable IT infrastructure resulting in the offices’ portal frequently being unavailable to professionals dealing with estates.

He said the offices fall within the Department of Justice and Constitutional Development which has now realised that rather than relying on contractors, it needs to recruit competent, qualified and skilful people to provide the tools that the offices require.

Confidence lost

Bongiwe Adonis, assistant manager at the Cape Town Master of the High Court, said the Master’s Office realised that practitioners and the public had lost confidence in it and that it needs to modernise its systems.

Online registration of deceased estates and trusts is one goal, and the aim is to have a user-friendly system like the South African Revenue Service’s eFiling system, enabling registration of an estate from anywhere in the world, she says.

But we are not there yet, an in the meantime, members of FISA, the Legal Practice Council and the South African Institute of Chartered Accountants can use a self-help system available at the Master’s Offices to register estates, she says.

The Master’s Offices have committed to processing applications registered this way within 10 days, Adonis says.

Estates that are not registered on this self-help system – for example when documents are couriered to the Masters Office have a 21-day turnaround time from the time, she said.

If the timeline is not met, the Master’s Office must explain the delay, she says.

Information is also being pulled from the Department of Home Affairs so that dependants can be identified and fraudulent activities minimised, Adonis says.

With these and other initiatives, the Master’s Offices are headed towards better and improved services by 2025, she says.

Source: FISA

Dec 2, 2022 | Article

Delport v Le Roux and Others [2022] ZAKZDHC 51

The applicant (D) brought an application under section 2(3) of the Wills Act, 7 of 1953 (the Act), asking the court to declare a document allegedly signed by the deceased (LR) as his last will and testament. The first respondent, the deceased’s estranged wife, had passed away by the time the case came to court. The second and third respondents (BR and BS) are the deceased’s daughters from a previous marriage, while the fourth respondent is the first respondent’s grandson who was adopted by the deceased and the first respondent. BR and BS opposed the application, while the fourth respondent did not. The fifth and sixth respondents, the Masters of The High Court in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng indicated that they will abide the decision of the court.

An accountant (SR) alleged in his affidavit that he drafted the document on instructions of the deceased and took it to the deceased, who signed it. SR then took the document to T, the wife of his business partner, and N to sign as witnesses. T and N were not in each other’s presence when they signed and neither of them was in the deceased’s presence when they signed as witnesses. It was therefore common cause that the document did not comply with the formality requirements for a valid will as provided for in section 2(1)(a) of the Act.

The lesson for fiduciary practitioners is to ensure that at all times that will documents are executed in strict accordance with the prescripts of section 2(1) of the Act.

In terms of s 2(1) of the Act the signature of the testator must be made in the presence of two or more competent witnesses. The witnesses must attest and sign the will in the presence of the testator and each other; where the testator signs the will with a mark, a commissioner of oaths must be present and specific certification formalities apply.

Sep 19, 2022 | Article

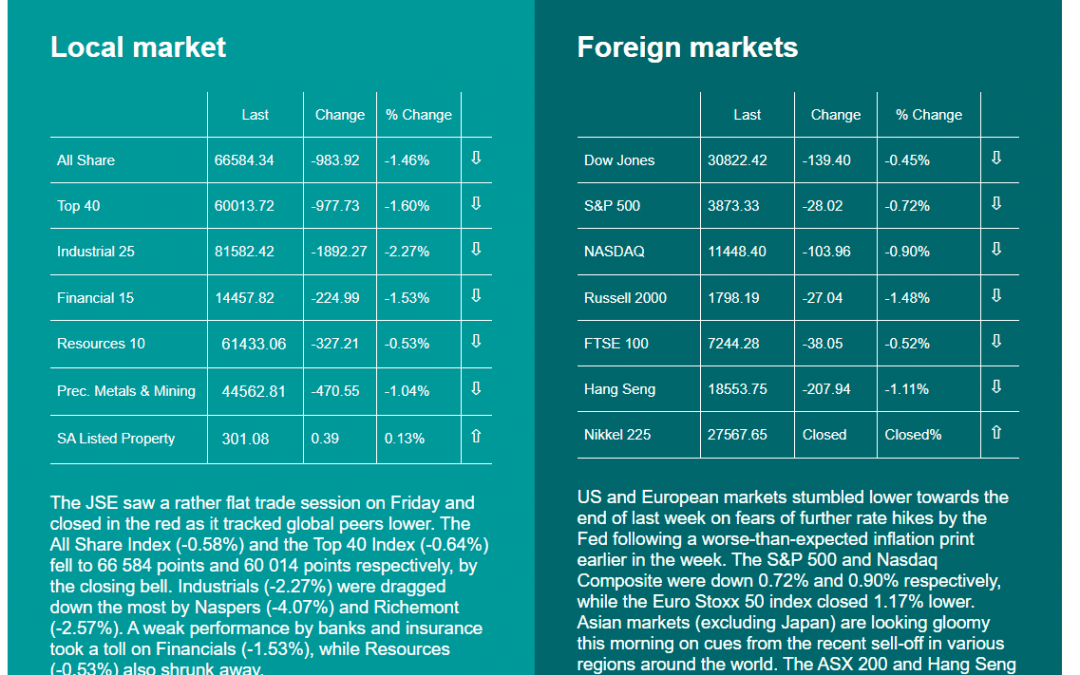

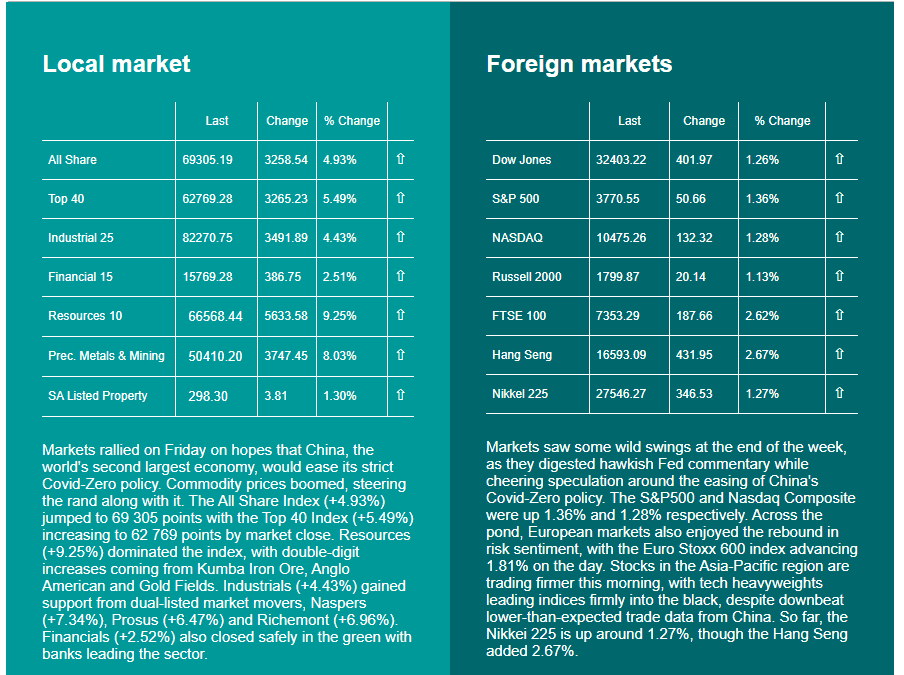

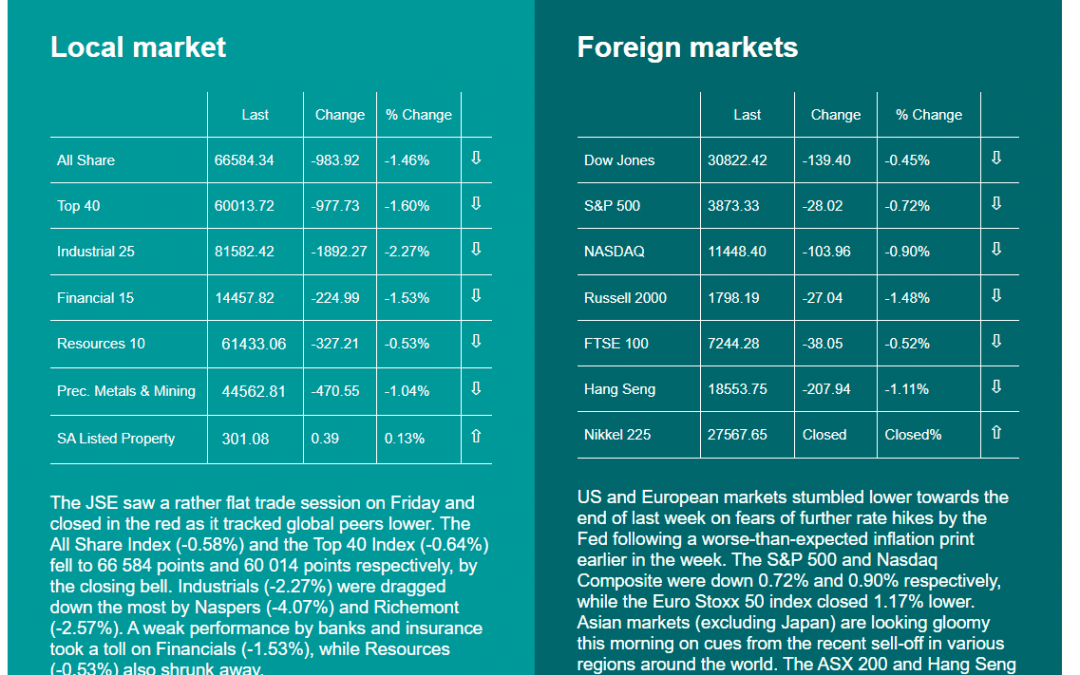

The JSE saw a rather flat trade session on Friday and closed in the red as it tracked global peers lower. The All Share Index (-0.58%) and the Top 40 Index (-0.64%) fell to 66 584 points and 60 014 points respectively, by the closing bell. Industrials (-2.27%) were dragged down the most by Naspers (-4.07%) and Richemont (-2.57%). A weak performance by banks and insurance took a toll on Financials (-1.53%), while Resources (-0.53%) also shrunk away.

US and European markets stumbled lower towards the end of last week on fears of further rate hikes by the Fed following a worse-than-expected inflation print earlier in the week. The S&P 500 and Nasdaq Composite were down 0.72% and 0.90% respectively, while the Euro Stoxx 50 index closed 1.17% lower. Asian markets (excluding Japan) are looking gloomy this morning on cues from the recent sell-off in various regions around the world. The ASX 200 and Hang Seng are trailing around 0.08% and 1.11% so far.

![Court case about trust assets and accrual upon divorce P A F v S C F [2022] ZASCA 101](https://agjenkins.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/AGJenkins-19.09.22a-1080x675.jpg)

Sep 19, 2022 | Article

The applicant (P) and the respondent (S) were married in 2001, out of community of property with inclusion of the accrual system. They were getting divorced in 2015. The divorce trial started on 18 February 2015.

Twenty days prior to the start of the trial P set up a trust in the British Virgin Islands (BVI) with their minor daughter as the only beneficiary and P’s brother, M, who was practising as a Queens Council in the BVI, as the only trustee. A day after the formation of the trust, P donated a sum of GBP115,000 to the trust. P’s version was that the trust was set up to cater for the minor daughter’s maintenance needs.

S averred that the setting up of the trust in the BVI was to make it more difficult for her to monitor the actions of the trustee or to take any action in case that was to become necessary. She also argued that the sum was placed in trust to frustrate her accrual claim. It was common cause that P’s estate experienced the greater accrual during the marriage.

The KwaZulu-Natal (Pietermaritzburg) High Court granted the divorce and ruled that the donation to the trust and the recording of an alleged loan by P’s father to him was done with the “fraudulent intention” to deprive S of her rightful accrual claim. The high court granted leave to appeal to a full bench of the KZN high court. The full bench dismissed the appeal.

P applied for special leave to appeal to the Supreme Court of Appeals (SCA). This application was done out of time and P had to apply for condonation of the late lodging of his application.

The SCA (Makgoka JA (Dambuza and Molemela JJA, and Makaula and Weiner AJJA concurring), held that there were no special circumstances why the late filing of the application should be condoned. The court also dealt with the prospects of success as part of the process and held that the timing of the setting up of the trust and the donation to the trust leads, in the absence of a reasonable explanation by P, to the conclusion that it was done to frustrate the accrual claim. The court also dealt with previous judgements about the nature of the court’s power to pierce the veneer of the trust and held that it is derived from common law and not from the Matrimonial Property Act or the Divorce Act.

As such the court held that the assets in the trust in the BVI should be taken into consideration in the calculation of the accrual claim. As there were no reasonable prospects of success, the late application for special leave to appeal to the SCA was dismissed with costs.

Sep 19, 2022 | Article

Some estate planners and trustees are not aware that a trust is regarded as a separate taxpayer, who has to register as such, and who has to submit relevant tax returns.

Trust income was always taxed in the hands of the trust unless it vested in the hands of the beneficiaries, whereby it was then taxed in the hands of the beneficiaries.

This practice was challenged in the CIR v Friedman case of 1993 on the grounds that the trust was not a taxable entity and, therefore, the trustees were not representative taxpayers. It was held in this case that, under common law, a trust is not a “person”.

This case resulted in the amendment to the definition of “person” in Section 1(1) of the Income Tax Act to include a trust and resulted in the inclusion of Section 25B in the Income Tax Act, which is a regulatory provision in the sense that it determines who will be taxed on trust income, and when, rather than being an anti-avoidance provision.

The principal taxing section for trusts

Section 25B of the Income Tax Act, which is the principal taxing section relating to trusts (subject to the anti-avoidance provisions of Section 7 of the Income Tax Act), provides that the income of a trust is taxed either in the trust or in the hands of the beneficiary as follows:

- If the income vests in a beneficiary during the financial year (ending February each year), then the beneficiary is taxed on it.

- If the income does not vest in the beneficiary, then the trust is taxed on it.

Section 25B of the Income Tax Act (referring to trust income) and Paragraph 80(2) of the Eighth Schedule to the Income Tax Act (referring to trust capital gains), read together with Section 7(1) (income distributed or vested but not yet paid) of the Income Tax Act essentially codified the Conduit Principle first articulated in South African common law.

That means that the Conduit Principle was first used without it being written into the Income Tax Act.

The Conduit Principle can only be used for taxing capital gains in the hands of the beneficiary if the trust instrument specifically gives the trustees the power to distribute a capital gain.

Wording to the following effect will empower the trustees to make a distribution of capital gains, which is an artificial concept in the Income Tax Act:

“…The trustees shall in their sole, absolute and unfettered discretion determine whether any distribution which represents the payment or distribution of any capital profit and/or capital gain arising out of the disposal of trust property, constitutes the vesting of an interest in the capital profit and/or capital gain in respect of that disposal for purposes of Paragraph 80(2) of the Eighth Schedule to the Income Tax Act 58 of 1962, as amended, irrespective of whether the amount actually distributed is lower or higher than the amount of the capital gain determined in respect of that disposal in terms of the Eighth Schedule to that Act.”

Do trusts pay provisional tax?

Trusts do not automatically qualify as provisional taxpayers in terms of Paragraph (1) of the Fourth Schedule to the Income Tax Act. They, therefore, must register with SARS as provisional taxpayers within twenty-one business days of becoming obliged to register – i.e. when they receive ‘income’ (note that this is a broader definition than ‘taxable income’).

Unless the trust distributes all income and/or capital gains in terms of the Conduit Principle discussed above, the trust will be liable to pay provisional taxes on amounts not distributed to beneficiaries or attributed to the funder.

All registered provisional taxpayers must submit a Provisional Tax Return (IRP6) and pay Provisional Tax twice a year in August and February each year. A top-up payment to pay 100% of the taxes due for that year may be made seven months after the year-end in August.

Provisional Tax is the only way that trusts would pay their taxes to SARS during the tax year if they earn taxable income. Although most trusts do not generate taxable income, SARS still requires nil income returns to be submitted.

If the trust does not qualify as a provisional taxpayer, but it derives a capital gain on the disposal of an asset during the year of assessment, then the receipt of the capital gain does not render it a provisional taxpayer.

When are trust tax returns due for submission?

Trust tax return due dates are in alignment with those of individuals. For this year the dates are as follows:

- Trusts that are not Provisional Taxpayers: 1 July 2022 to 24 October 2022; and

- Trusts that are Provisional Taxpayers: 1 July 2022 to 23 January 2023.

Source: Phia van der Spuy

![Court case about trust assets and accrual upon divorce P A F v S C F [2022] ZASCA 101](https://agjenkins.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/AGJenkins-19.09.22a-1080x675.jpg)

Recent Comments