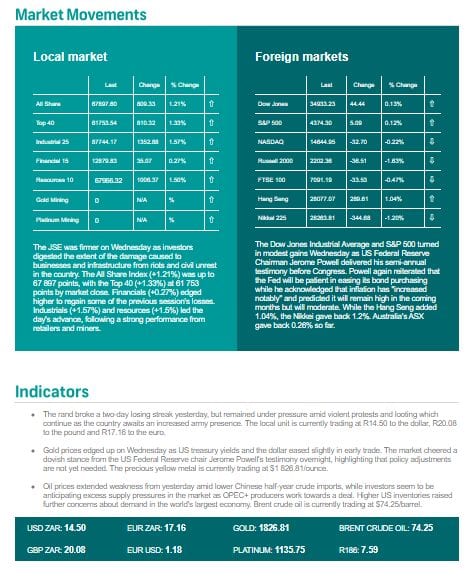

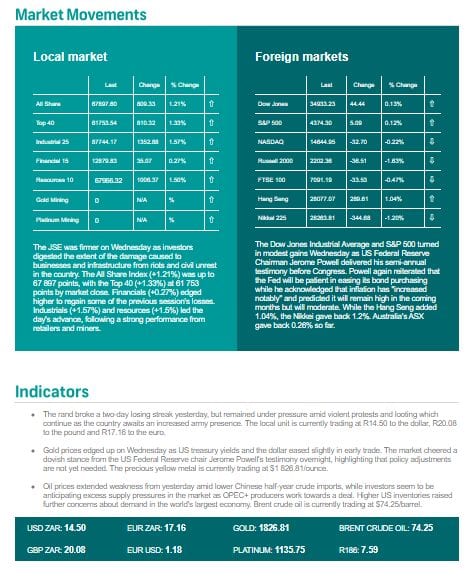

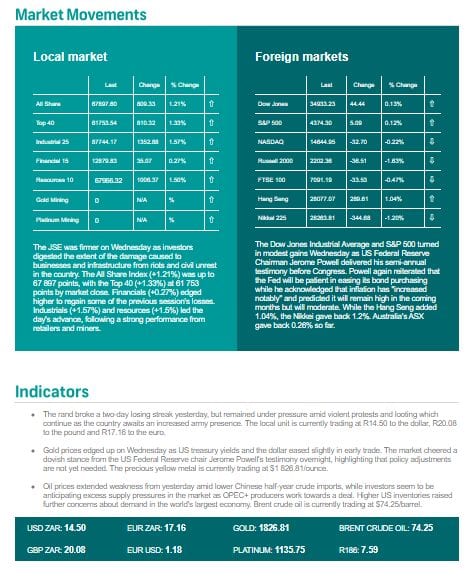

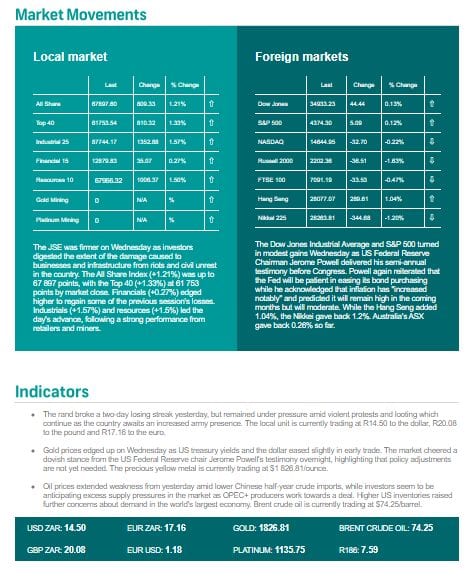

The local markets recovered somewhat yesterday, but the Rand is till under pressure …

This is a very useful article by Phia van der Spuy and it is important to bear in mind the Transfer Duty implications for the acquirer of immovable property from the Trustees in certain circumstance.

TRANSFER Duty is an indirect tax levied on the acquisition of fixed property in South Africa.

It is payable on the value of any property acquired by a person by way of a transaction or in any other manner. Transfer Duty is not payable on the transfer of the property that gave rise to Transfer Duty.

Instead, it is the acquisition of the personal right by the purchaser against the seller that gives rise to the Transfer Duty obligation. The Court held in the CIR versus Freddies Consolidated Mines Ltd case of 1957 that the word “acquired” (which is required for a “transaction” to take place under the Transfer Duty Act) means the acquisition of a “right to acquire ownership in a property”.

The judge confirmed in the SIR versus Hartzenberg case of 1966 that Transfer Duty becomes payable upon the acquisition by a person of a personal right to obtain dominium (ownership and control) in immovable property.

With a vesting trust where the beneficiary has a vested right in the trust income (both of a revenue and capital nature) and/or capital in terms of the trust instrument, or a discretionary trust where the trustees exercised their discretion in favour of the beneficiary and the beneficiary obtained a vested right in the trust capital, they will obtain only a personal right against the trustees.

No Transfer Duty is payable when a beneficiary obtains a personal right from the vesting of trust capital because no specific property was vested. Even though a beneficiary may have a vested right in trust capital, the trustees may (if they are entitled to do so under the provisions of the trust instrument) decide to sell the property (and even buy another in its place). In this case, it is clear that the beneficiary never had a real right in either of the properties while they were registered in the names of the trustees.

Only when the trustees decide to transfer a property to a beneficiary do they acquire a real right. This might never happen if the trustees decide to sell and convert the property into cash and then distribute such cash to the beneficiaries. The beneficiary will obtain a real right in the trust asset as soon as ownership in such asset is transferred to the beneficiary. If property is transferred to the beneficiary, they will be liable for Transfer Duty once it is transferred.

In the event of the trustees electing to vest immovable property in the name of a beneficiary of an ownership inter vivos trust (which includes a vesting trust and a discretionary trust) by transferring the property into the name of that beneficiary in the Deeds Registry, the transfer is exempt from Transfer Duty provided the beneficiary is related to the founder or creator of the trust by blood within three degrees of consanguinity and the beneficiary paid no consideration (directly or indirectly) for the property (Section 9(4)(b) of the Transfer Duty Act).

In the event of the trustees electing to vest immovable property in the name of a beneficiary of a testamentary trust by transferring the property into the name of that beneficiary in the Deeds Registry, the transfer is exempt from Transfer Duty provided the beneficiary is entitled to it under the will in terms of which the trust was set up. (Section 9(4)(b) of the Transfer Duty Act).

Beneficiaries are not the owners of the trust assets in an ownership trust (which includes a vesting trust and a discretionary trust), but have a vested right with regard to any capital distributed by the trustees.

If a beneficiary disposes of this right, it is not a “real right in land” or a “contingent right in a discretionary trust” and, therefore, does not fall within the ambit of “property” as defined in Section 1 of the Transfer Duty Act.

However, when a beneficiary disposes of their contingent right in a discretionary trust – such as when beneficiaries are substituted during the amendment of a trust instrument – not only may it be argued that a new trust may have come into existence as a result thereof (with Capital Gains Tax and other potential tax consequences), but it may trigger Transfer Duty as a result of the “substitution or addition of one or more beneficiaries with a contingent right to any property of that trust, which constitutes residential property”(Section 1 of the Transfer Duty Act).

Since there is no definition of “residential property trust”, the provisions would apply to a trust owning residential property regardless of the proportion of such property to the full value of the assets held by the trust. In this instance, the Transfer Duty is based on the full market value of the residential property, regardless of the interest the person acquires in the trust.

Therefore, any indirect transfer of immovable residential property (primarily to avoid Transfer Duty) becomes taxable in the same manner as any direct transfer of the property out of the trust.

![Court case: Handwritten document not intended to be a will – Osman and Others v Nana N.O and Another [2021]](https://agjenkins.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/agjenkins-Article-court-case-1080x675.jpg)

Osman and Others v Nana N.O and Another [2021] ZAGPJHC 47

The deceased (S) died in April 2018, apparently without a valid will. He was a medical doctor. The first respondent (N), one of the daughters of S, was appointed as executor of the deceased estate by the Master of the High Court at the end of June 2018. Under intestate succession N and her siblings would be the only heirs of the residue of the deceased estate. The eighth appellant, Y, is the son of one of S’s sisters. On 1 August 2018 Y searched the former home of S and found a document entitled “Notes on will” dated 14 August 1990. The document was handwritten and unsigned.

The sisters of S brought an application to have the handwritten and unsigned document declared a valid will under the provisions of section 2(3) of the Wills Act, 7 of 1953. The section reads:

“If a court is satisfied that a document or the amendment of a document drafted or executed by a person who has died since the drafting or execution thereof, was intended to be his will or an amendment of his will, the court shall order the Master to accept that document, or that document as amended, for the purposes of the Administration of Estates Act, 1965 (Act No. 66 of 1965), as a will, although it does not comply with all the formalities for the execution or amendment of wills referred to in subsection (1).”

The court a quo (Matojane J) dismissed the application and ordered costs to be paid from the deceased estate. The court held that although it was not in dispute that S wrote the document in his own hand and therefore drafted the document, there is no evidence that he intended the document to be his will. Therefore the second requirement of section 2(3) was not fulfilled.

On appeal to a full bench of the Gauteng High Court, the court (Meyer J (Windell and Twala JJ concurring) dismissed the appeal with costs. The court was critical of the lack of evidence and failure to supply facts supporting the notion that S intended the document to be his will and the fact that the appeal was aimed against the whole of the court a quo’s judgement and order.

A sperm donor has failed in his bid to have contact with the child he ‘fathered’. This is the effect of a ruling by Gauteng High Court (Pretoria) in an unusual battle in which the donor and his mother sought visitation rights for the now five-year-old child. The application was dismissed with costs.

The application was strongly opposed by the child’s parents, a same-sex couple who underwent artificial insemination to enable one of them to conceive. The judge said while the applicant, whom he referred to as QG, and his biological grandmother may well love and feel a strong bond with the child, that did not give them the right to interfere in ‘the little special place (the respondents) have created for themselves’. ‘While it may appear to be harsh, that is ultimately what is needed to respect and protect the intention and choice of the respondents in constituting their family.

The applicant, an interior decorator, brought the application in two parts.

The first, which was dealt with by the Judge, was for visitation rights.

The second will be launched after a still-to-be-held inquiry by the Family Advocate.

In that, QG wants rights of contact and care and joint guardianship. In his application QG did not rely on a ‘biological right’, but on the bond. This because SA law is clear that sperm donors do not have any rights. ‘This legal certainty is essential for sustaining the artificial reproductive system in SA. If this is compromised, donors would not be willing to donate, recipients would not be willing to accept donations and infertility would become an unsolvable burden,’ the Judge said.

The judge said it was clear when the agreement was reached, no role was envisaged for the applicant in the child’s life. ‘They say, and this is not unreasonable, that out of a sense of gratitude they allowed him to have some limited contact with the child, but they did not open the door to the kind of rights he now seeks.’ noted the Judge.

‘It must be so that a family is often about intimate space and special bonds. While that space may be open to scrutiny when it involves the best-interests-of-the-child principal, it is also a space that requires protection and insulation from undue outside influence. It is a far stretch to suggest that someone, who out of goodwill and gratitude reaches out and is warm and inviting to another, must then carry the consequences that such conduct may trigger a rights claim on the part of the other.

This is not tenable and were it allowed it would have a chilling effect on ordinary human relations,’ the judge said. Regarding QG’s claim that the child needed a father figure, the Judge said the focus should be the environment of love and caring created for the child, not the sexual orientation of its parents.

(Source: LegalBrief)

Estate Duty is a material ‘death tax’ that very few people take cognisance of. Luckily, in terms of Section 4(q) of the Estate Duty Act, but subject to its strict requirements, relief is provided to surviving ‘spouses’ who may have contributed to the accumulation of their assets, by allowing a deduction of the value of all property, which accrues to the surviving spouse, from the gross estate of the deceased. No Estate Duty is therefore payable on qualifying assets.

This provides some relief for surviving ‘spouses’ who may end up having to part with assets they used to share with their spouses, just to pay Sar’s tax bill. The definition of ‘spouse’ for this purpose includes a permanent life partner and not only a legal spouse in terms of the Marriage Act or the Civil Union Act. People are advised that this deduction can also be applied when a trust is set up to basically avoid/bypass Estate Duty. Such a structure is commonly referred to as a “Widow’s Trust”.

Section 4(q) was however cleverly crafted by Sars and people will be ill-advised to take such advice, which may leave you ‘out-of-pocket’ upon your spouse’s death if you have not made provision for this tax. The purpose of this section is only to postpone the payment of Estate Duty and not the avoidance thereof.

When the section is carefully analysed, the following is important to successfully utilise this ‘rollover’ (postponement) of the Estate Duty obligation until the surviving spouse’s death:

· The phrase “accrues to the surviving spouse” means that the surviving ‘spouse’ may receive the assets either in terms of the deceased’s will, or through intestate succession.

The following is clear from the wording:

Any incorrect advise may have dire consequences, which may leave a large cash flow gap (20% to 25% of such assets) if Sars disallows a Section 4(q) Estate Duty ‘rollover’.

~ Written by Phia van der Spuy ~

The Rand in tandem with South African stocks retreated yesterday, tracking declines in emerging-market peers as the US Federal Reserve’s hawkish turn hurt appetite for riskier assets. The Rand slid to R14.16 to the greenback yesterday and is currently trading at R14.07. Major miners were a big drag on the benchmark equity index as a stronger Dollar hit metals prices. The FTSE/JSE Africa All Share Index slipped 0.7% in Johannesburg yesterday, falling for a second day as trading resumed after Wednesday’s public holiday.

Locally, investors are awaiting retail sales data for April and assessing the impact of tighter restrictions aimed at countering soaring Covid-19 infection rates. Anglo American dropped 2%, to cause the largest drag on the benchmark gauge, and BHP fell 1.1% as an index of industrial-metals miners slid 1.5%, declining for a third session. A gauge of precious-metals producers dropped 2.8%, falling for an eighth day in the worst losing streak since February 2018, after gold capped the biggest drop in five months. Foreign investors have continued a recent spate of selling South African equities, disposing of a net R601 million of local stocks on Tuesday, according to the JSE, marking an eighth day of outflows. (Source: E Biz Blitz/Bloomberg)

Recent Comments